A New Understanding of Mortality and Death

Reflecting on The Fuji Declaration

A new phase in the evolution of human civilization is on the horizon. With deepening states of crisis bringing unrest to all parts of the world, there is a growing need for change in our ways of thinking and acting.

I am writing with full support for the Fuji Declaration. It represents a positive and life affirming vision that can move us beyond the crisis and unrest that we face as a global civilization.

- How is our way of thinking and acting needing to evolve in regard to the most basic aspect of our existence: human mortality

Why, we might ask, is there such a fear around death? What has made death the great taboo topic, in spite of the fact that we all die?

The famed writer Mark Twain suggested this answer: “The fear of death follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time.”

Ernest Becker spent a significant portion of his career seeking to understand the fear of death. While he was a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, he published his seminal and Pulitzer Prize–winning work, The Denial of Death. With this book, he awakened a conversation about the cultural meanings of death. Becker saw the endemic denial of death as a source of pathology in our modern world.

“In our culture we have done a tremendous amount to deny our own mortality and in that process we have been initiated into a kind of pathological social organization,” Becker wrote. He saw the fundamental motivation for human behavior as a biological need to control our basic anxiety of death. “This is the terror to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self- expression—and with all this yet to die.”

- What are the consequences of not facing the reality of mortality in constructive ways?

As I discuss in my book, Death Makes Life Possible (2015), Becker’s work and theory about death denial has catalyzed decades of research by social psychologists on what is called terror management theory (TMT). This theory proposes that a basic psychological conflict results from having a desire to live but realizing that death is inevitable. This conflict produces terror, and this terror is believed to be unique to human beings. Each of us, according to TMT, is holding this suppressed death terror, largely at an unconscious level. In other words, we are not aware of the fear. To buffer ourselves against death terror, we seek to boost our self- esteem by affiliating with cultures or groups whose values provide our lives with meaning. For example, religious affiliation is a strong factor in Becker’s model (for example, if you are Christian, or Hindu, or Jewish, you will affiliate with people of the same faith tradition). As we are confronted with our own mortality—or, in psychological terms, as our mortality salience increases—the theory predicts that we may become more aggressive and violent to other groups that hold different opinions, values, and worldviews than our own. At the same time, we may identify even more strongly with our “in-group,” which offers us a greater sense of social support and security against outside threats. Death awareness can be a tool of peace in the context of myriad global conflicts.

- How might a new understanding of mortality and death reveal ways of nurturing and renewing our natural world?

Cultivating death awareness in the context of positive self-esteem and an appreciation for diverse perspectives or worldviews can lead to less fear and anxiety and reduce violence and aggression towards others. In a certain sense, it’s fair to say we can advance peace through death awareness. As we embrace our embeddedness in nature, we find ourselves able to nurture and renew our relationship to the social and physical worlds of which we are a part.

- What does your research on mortality and death suggest about our true nature?

While we have our own individuality, at our fundamental level we are all interconnected. Birth and death are aspects of a whole life that is beyond our individual identities.

- ** What helps people face death with greater courage and grace?

The studies of Terror Management Theory show that reminders of death can be both personally unsettling and socially disruptive. And yet there appear to be ways in which our awareness of death can lead to positive psychological and behavioral outcomes. There is ample evidence to suggest that people may grow, stay true to their values and build loving relationships when they address their death concerns. Ultimately, it can lead people to be happier, healthier, and better citizens.

- Does your research shed further light on the question of an invisible force that informs and shapes our material/mortal existence?

Consciously transforming our worldviews involves appreciating the ways in which we experience what it means to be human. Our worldviews about death are a key to understanding our own identity and what happens to it when we are no longer embodied. As we begin to understand and dive more deeply into death as a rich and complex component of life, we have an opportunity to look at our own assumptions, beliefs, and expectations. Indeed, looking at how we view death is a way of seeing how we may overcome our fear of it to live more deeply. In turn, how we view death often mirrors how we transform and change throughout our lives.

- How might a new understanding of mortality and physical death transform our understanding of being part of a larger living field?

In my work on Death Makes Life Possible, both the film and the book, I have approached the topic of our mortality from a wide variety of beliefs and worldviews. Each of us can learn to better understand and appreciate our own worldview and those of others. Harnessing our capacities to listen and examine multiple perspectives with humility and curiosity can open us to new ways of being. As we explore worldviews, we have a chance to not only reflect upon, comprehend, and communicate our own worldview, but also to recognize that our beliefs come from our particular life experiences and personal values. We may learn to better appreciate that other people hold different and potentially equally valid models of reality out of which their assumptions and actions arise. This capacity to appreciate other worldviews involves the growth of our own cognitive and cultural flexibility. It compels us to draw on our deepest creativity and resilience in the face of differing points of view. Improving our worldview literacy prepares us to adapt to new insights that come when we encounter different perspectives, customs, practices, and belief systems. At the most fundamental level, worldview literacy allows us to bring awareness to what is true for each of us about life, death, and what may lie beyond. It is a celebration of life.

- ** What appears to be the benefit for the people you have met who face death with less fear?

Transforming the fear of death can become an inspiration for living and dying well. It helps us heal the deepest pain and source of suffering. And, it takes practice.

- How does your research restore awareness of a divine spark within each of us? Is there language, scientific and secular in nature, that reflects similar understandings found in spiritual literature?

Many people report experiences that suggest an extended reach of our human consciousness, including near-death experiences, spontaneous healing, or other phenomena that arise in nonordinary states of consciousness (such as seeing apparitions, sensing oneness with the whole of existence, or having precognitive dreams). Transpersonal scholar and archivist Rhea White found that even though the phenomenology of such experiences may differ, all can serve as portals to a new worldview that embraces oneness with all of life, interconnectedness, and prosocial values. These breakthrough experiences can be puzzling for people. While there may be no external “proof” to validate or explain many such experiences, they can be powerful and life transforming.

- ** When you think over your research and the many people you interviewed, what were some of the most inspiring messages and insights you found about how we can overcome our fear of death?

My work has led me to consider diverse paths of exploration that can help heal our fragmented lives. These include insights from diverse cultural, religious, and spiritual traditions; science; and a variety of transformative practices that lead to direct personal experiences with expanded states of consciousness.

In the spirit of the Fuji Declaration, there is an emerging new worldview that links this inner wisdom with a science of entanglement and quantum physics, leading to the emergence of an evidence-based spirituality. This emerging worldview, grounded in death awareness, offers people comfort in the face of their own death and that of their loved one’s mortality.

Recognizing our interconnectedness can give us a larger framework in which to see ourselves in relationship to others—both living and departed—and can lead us to the spirit of service to others. Transforming our fear of death can result in the development of greater kindness, generosity, love, compassion, forgiveness, and altruism. Further, it can expand our sense of community and make it more inclusive, as we drop the illusion of the “other” and more fully recognize our fundamental interdependence with all of life.

We may notice that we become less reactive to people whose worldview is different from our own, regarding them instead with curiosity and appreciation for our common path as mortal beings. Overcoming the fear of death can help us to live more fully and deeply.

Transforming our worldview around death can also be applied to the development of more sustainable social practices. Revising the assumptions and the policies that guide our shared social and cultural values around death may lead us to full-systems change. As a critical mass of people is able to transform their collective pathology around death, we may revise how our social institutions, in particular healthcare, treat death and dying. We may achieve a tipping point that serves our collective wellbeing. In this way, we may integrate our own inner transformation with the evolving cultural landscape of which we are co-creators.

30/04/25

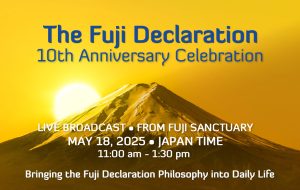

The Fuji Declaration was launched in May 2015 during a grand inauguration ceremony at Fuji Sanctuary. Since th[...]

09/05/24

The Fuji Declaration was launched in May of 2015 during a grand inauguration ceremony at Fuji Sanctuary. Since[...]

29/04/24

The Fuji Declaration will celebrate it’s 10th anniversary next May. Starting on this 9th anniversary and conti[...]

30/01/24

This year, as part of the Fuji Declaration 9th Anniversary Program, we will conduct a program with you to delv[...]

09/05/23

The Fuji Declaration 8th Anniversary Celebration At Symphony of Peace Prayers Fuji Sanctuary Japan May 21st, 2[...]

27/04/22

The Fuji Declaration 7th Anniversary Celebration At Symphony of Peace Prayers Fuji Sanctuary Japan May 15th, 2[...]

26/04/22

The Fuji Declaration initiative was launched in 2015 together with over 60 partner organizations and 200 honor[...]

07/01/22

The three co-initiators of the Fuji Declaration, Ervin Laszlo, Hiroo and Masami Saionji, invite you to watch t[...]